During the Prohibition era (1920–1933) in the United States, the federal government undertook a drastic and highly controversial approach to deter illegal drinking. Known as the "poisoned alcohol program," this policy involved intentionally contaminating industrial alcohol with toxic chemicals to discourage its consumption by bootleggers and the general public.

The Context

Prohibition made the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcohol illegal. However, Americans continued to drink in large numbers, purchasing illicit alcohol from bootleggers and speakeasies. A significant portion of this illegal supply came from industrial alcohol—a type of alcohol legally used in products such as cleaning supplies, fuel, and medicine. Bootleggers would steal, redistill, and sell it as drinkable alcohol.

To address this problem, the federal government implemented stricter regulations requiring manufacturers to "denature" industrial alcohol. Denaturing involved adding chemicals to make the alcohol undrinkable. While this practice existed before Prohibition, the government escalated the program in the mid-1920s by mandating the addition of highly toxic substances, such as methanol (wood alcohol), kerosene, benzene, chloroform, and acetone.

The Consequences

Despite the increased risk, many people continued to drink the tainted alcohol. The results were devastating:

By 1927, reports indicated that over 10,000 people had died due to consuming poisoned alcohol during Prohibition.

Thousands more suffered severe health effects, including blindness, organ failure, and long-term neurological damage, as a result of methanol poisoning.

Health professionals and reformers condemned the program, arguing that the government had effectively engaged in a policy of intentional harm. Doctors in major cities saw a sharp rise in patients suffering from alcohol poisoning, and many described the effects as horrific. Critics labeled the program a "murderous attempt" to enforce Prohibition, with headlines decrying the federal government’s willingness to poison its own citizens.

Public Outcry and the Fallout

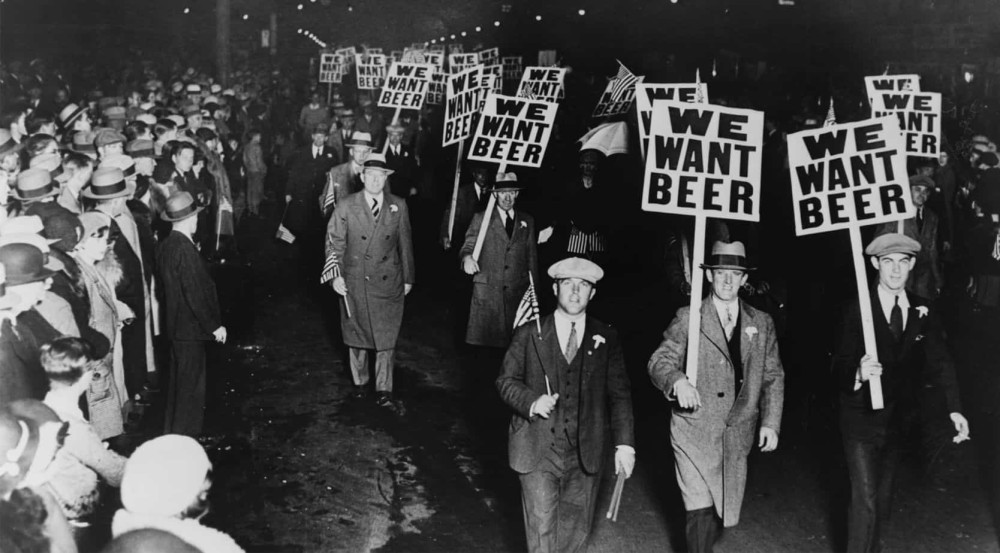

The poisoned alcohol program became a public scandal, further eroding support for Prohibition. Many Americans saw the policy as evidence of the government’s inability to manage the unintended consequences of the alcohol ban. The Prohibition enforcement effort was increasingly viewed as draconian and ineffective, contributing to the growing momentum for its repeal.

By 1933, the Prohibition experiment came to an end with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment. The poisoned alcohol program remains a dark and controversial chapter in U.S. history, serving as a reminder of the dangers of overreach in the pursuit of moral legislation.

Legacy

Today, the poisoned alcohol program is often cited as one of the most extreme examples of a government policy with deadly unintended consequences. It highlights the lengths to which officials were willing to go to enforce Prohibition, regardless of the human cost. This chilling chapter underscores the risks of imposing laws on an unwilling public and the devastating effects of prioritizing enforcement over public health and safety.